Let’s make a canon! And let’s fill it with queer art, or queer-ish art, or art that has no idea how queer it is. Queer art is often secret art: black-market, whispered-about, read-between-the-lines art. And since secret art can be hard to find, let’s shine a light on a few of our favourite things so all our friends can see them.

We’ll call it a canon, because it sounds Weighty and Important and Serious, but we also won’t be too serious about it. We won’t make The Canon, just a canon. Each month, we’ll chat with a different queer-about-town and ask them to submit something to the canon. And they’ll tell us what that book or play or movie or TV episode or sculpture or poem or dance piece or opera or photograph or painting or performance art piece or anything else means to them and why they think it deserves a spot in our illustrious canon.

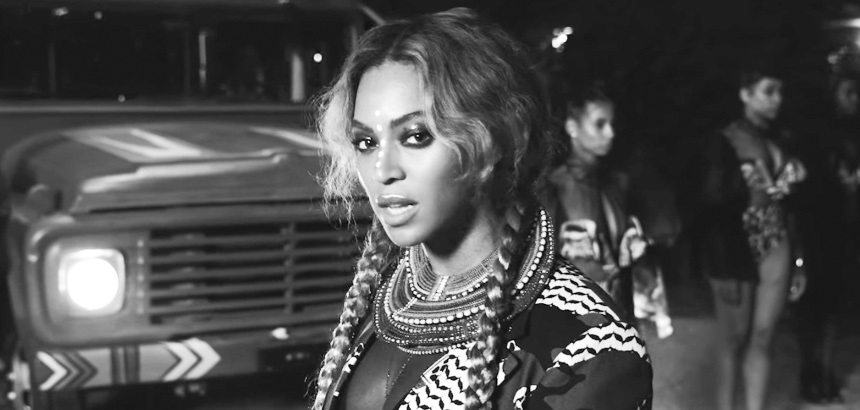

This month, we talked to author, musician, and filmmaker Vivek Shraya about Beyoncé’s “Sorry.”

So what are we talking about today?

I’ve been thinking a lot about your project, and for me, I saw it as an opportunity to think of the queer canon creatively. And so one of the things that’s I’ve thought about (starts laughing) and it’s a bit of a reach! So, Lemonade. Beyoncé.

Yep.

The song “Sorry.” Which, of course, is by a black woman and about her black experience, and I don’t wanna appropriate that, but when I think about the queer canon, I think sometimes we have to be creative about where we find resonance. Because of the absence of people telling our stories or the absence of role models. And for me, the lyrics in “Sorry,” particularly when she says “Boy, bye!” and “I ain’t thinkin’ ‘bout you!”—as I’ve been transitioning, “Sorry” has felt a bit like a trans anthem.

OK! That’s really interesting, I like that!

Any time when I’m struggling with the process, I put on “Sorry.”

Obviously, Beyoncé has a huge queer following in general. I feel like almost everything she says becomes a sort of queer rallying cry, right?

Totally! And again, I was nervous about bringing this to the table, because I’m also always wanting to be respectful about the fact that Lemonade in particular has been talked about as being connected to black culture. But I think the flipside is: what are trans anthems? What might be trans anthems? And that song in particular has made me think about how breakup songs can be trans anthems. Because for me, that’s what transitioning has felt like: breaking up with a gender that I never really associated with.

I never thought about the idea of breaking up with your gender, but that’s a really interesting concept. What did you feel about the film Lemonade? Because in a way, they feel indivisible—the songs and the visuals.

I was thinking a lot about the “Sorry” video, and I think Serena Williams is also a huge queer icon. One of the things I’ve been struggling with is: in my efforts to be a boy, that meant muscle. Especially in the gay community, there’s so much pressure to be masculine, and masculine means muscular. So, I’ve spent fifteen years lifting weights. And now, shopping for feminine clothing, it’s really difficult. Because it’s really about being tiny. And the bigger the size gets, the less colourful it becomes, and it’s more about hiding your body. When I go shopping, it’s really hard to push against the feeling that I need to go sit on a treadmill for a day. Or a lifetime. And I’ve already done that with masculinity. I spent so much time in the gym, trying to prove my maleness. So now it’s like, fuck, I don’t wanna have to prove my femininity just by my appearance. And Serena, looking at her and just the sorta way she carries herself in her body, it reminds me that there are many ways to be feminine.

Lemonade is so interesting, because we know so much of it is about the black experience in America, but it’s also about Beyoncé’s marriage and her relationship to her father.

I feel like it’s her most personal album. In a way, the most shocking thing she could do at this point is be vulnerable. When I listen to “Sorry,” there’s a deep sadness to that song. She’s like “I’m not thinking about you, suck my balls, call Becky with the good hair…” but there’s also this undercurrent of pain there. I think one of the hard narratives around transition is that there’s this clear beginning, middle, and end. And I think that there are things about my masculinity that—as much as it’s felt performative most of my life—I’ve grown to like. A simple trans narrative is, I was assigned male at birth, I was “in the wrong body,” and now I have found the truth. And some trans people really connect to that narrative. But it’s been so much more complicated for me than that. I do feel like a weight has been lifted by having people call me “she” and “her.” But at the same time, there is a sort of feeling of “Can I still perform masculinity if I want? Do I have to perform femininity? Do I have to show up to this interview wearing makeup for you to see me as I want you to see me?” There’s this pain there, and going back to the song, that’s something that really resonates. On the surface, it’s this breakup, tough song. But for me when I hear it, there’s also this sadness.