A crash course in the two-way street of fascination between queer and catholic and the tense relationship between the sacred and the profane.

Beneath every image of the sacred is an armature for the profane. No matter the religious iconography every quality painted in a virtuous light—when taken to extremes—can easily become audacious and obscene. In particular, the representational history of Catholicism is replete with motifs of shame, self-sacrifice, punishment and denial. As early as the 15th century, Flemish painters were representing holy figures as largely shapeless, sexless and grief-stricken bodies posed in contorted manners or in uncomfortably tight pictorial space.

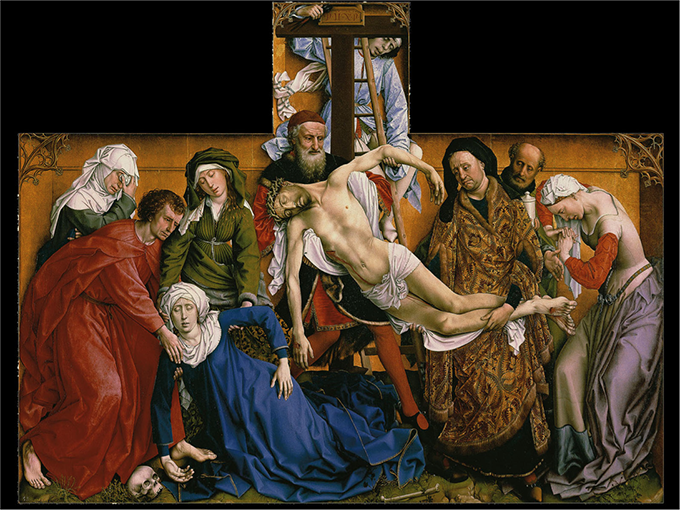

These qualities are perhaps the most obvious in Rogier van der Weyden’s Deposition—a massive altarpiece showing the lowering of Christ’s body from the cross. On top of the wincingly shallow sense of space, none of the figures appear to acknowledge one another or even address the viewer by looking out from the picture plane. The incredible suffering of this moment in the story of Christ would assume a frenzy of emotion and visceral grief. However, Weyden’s popular interpretation of the scene is in fact lifeless, and even vulgar, in its distanced and clinical depiction.

Rogier van der Weyden Deposition c. 1435-1438, oil on panel, 7’2” x 8’7” (2.2 x 2.62 m)

These paradoxes were of great interest to the members of Grupo Chaclacayo (1983-1994)—undoubtedly the most radical art collective to emerge in Peru during the 1980s. The group formed during the midst of a violent conflict involving the Peruvian government and communist revolutionaries—one that would leave 70,000 dead in its aftermath.

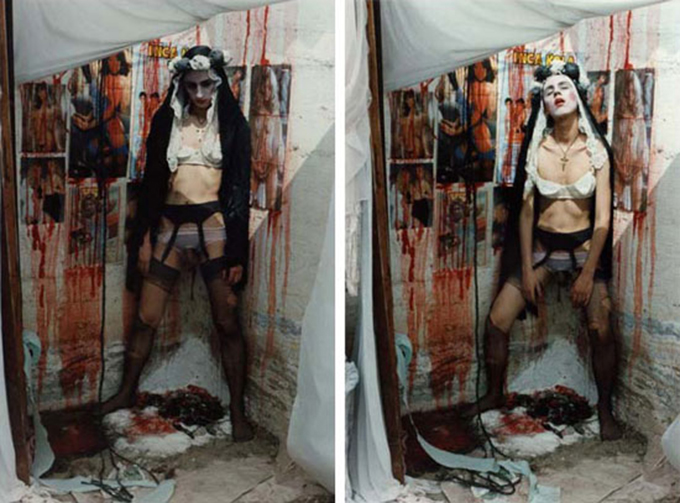

Consisting of Helmut Psotta, an immigrant German, and his two Peruvian students Sergio Zevallos and Raul Avellaneda, Grupo Chaclacayo created an immense oeuvre of queering Catholic iconography through performance, photography and installation. Their work has often been described as “deeply transgressive” and Miguel A. López writing in e-flux pronounced their oeuvre as “an experiment in the production of abnormal and deviant subjectivities that undid gender and social identities.”

Sergio Zevallos (Grupo Chaclacayo), in collaboration with Frido Martin, Rosa Cordis, 1986. Retrieved from eflux.com

Grupo Chaclacayo had such an emphatically othering quality to their work because they challenged the ‘natural’ (i.e. dominant) vocabulary of Latin Catholicism with explicit visual narratives of sex, sadomasochism, murder and madness. Central to this psychotic juxtaposition was always their own queerness and the recurrence of the transvestite as an allegorical figure. Often combining nuns robes with women’s lingerie, and occasionally prosthetics, their work fought to sexualize and reclaim the symbolically castrated bodies of Catholicism.It was a direct critique of the sterilizing ideology that their own State continued to employ throughout the civil conflict.

The core imagery of the Catholic transvestite in Grupo Chaclacayo’s work is also echoed in the confessional androgyny of Michel Tremblay’s Manon, Sandra and the Virgin Mary. The audience bears ‘holy’ witness to the montage of sacred Manon and profane Sandra. Their mirror-image relationship is played out through the symbolic (and necessary) conflict of drag. The pious Manon’s exaggerated innocence finds its equal in the decadent sexuality of Sandra, and together they allow the sacred cycle of the profanity known as “life” to carry on.

It was the weight of this cycle that eventually brought an end to Grupo Chaclacayo. Their work was motivated by a dominant and oppressive ideology—to which they valiantly protested and subverted. However, this also meant that their entire body of work was dependent upon a combative relationship with the Catholic aesthetic. Art of that nature is hard to sustain, and as times changed in Peru the relevancy of their inverted iconographies faded.

Oddly enough [insert sarcasm], despite its cultural value, Grupo Chaclacayo’s work is rarely seen and largely unknown on an international scale. Perhaps the blatant nature of the imagery is a little ‘too much’ for most galleries and museums to mount? Or, it could be the fact many of Grupo’s works now exist outside Peru and the generation that lived through their work? Either way and akin to Manon…, which is also rarely performed, works that bridge the gap between sacred and profane often endure a kind of quarantine specific to essential paradoxes. Just like humanity doesn’t especially like to recognize the evil in the good (only the other way around) we as a society have a hard time recognizing that the sacred has no meaning without profanity as its mirror. And, without works of art and theatre of this nature we may fail to recognize it at all.