In the context of Canadian culture, I tend to associate heritage with “Dr. Penfield, I can smell burnt toast.” That is, institutionally-endorsed moments wherein Canadians prove themselves to be somehow exemplary—especially compared to Americans and the British. Heritage has a nostalgic filter and a very small aperture.

In the theatrical context created by Damien Atkins, Paul Dunn, and Andrew Kushnir, heritage is an unstable thing; still made of moments, but constantly aware of what each moment leads to or from. Theirs is a legacy that requires ordering.

Organization is a palpable theme running through The Gay Heritage Project, which at nearly two hours never ceases to entertain, delight, and move, even as it splits off into ever more specific investigations of categories, and the way those categories both do and don’t intersect.

It’s also a show about something—not exactly documentary theatre, but certainly aware of its framing device. Beyond that framing device, The Gay Heritage Project is about three gay men—friends, partners, and colleagues—who decided to create a performance out of an extremely diffuse archive. As their research takes them into historical, political, and personal regions, gay heritage shows itself to be less and less cohesive. For instance, the very naming of gay identity is a modern idea, as revealed through Atkins’s hypothetical dialogue with an ancient Greek. As the creators chip away at what it means to historicize gayness, they consistently come up against erasure, and of course, torment.

Heritage as a choice is a central thesis of the show, and over its five acts, Dunn, Atkins, and Kushnir make a lot of them. Heartfelt and hilariously funny as each scene often is, there’s a tension spanning the acts that isn’t always easy to locate. It has something to do with the choosing, I think. Each time the performers continue to name things that are (and on occasion) are not gay, an awareness grows of the things that are unnamable, or adjacently connected to the issue of gay heritage. Each scene often reaches a point of frustration, as notions of heritage pull closer and then recede.

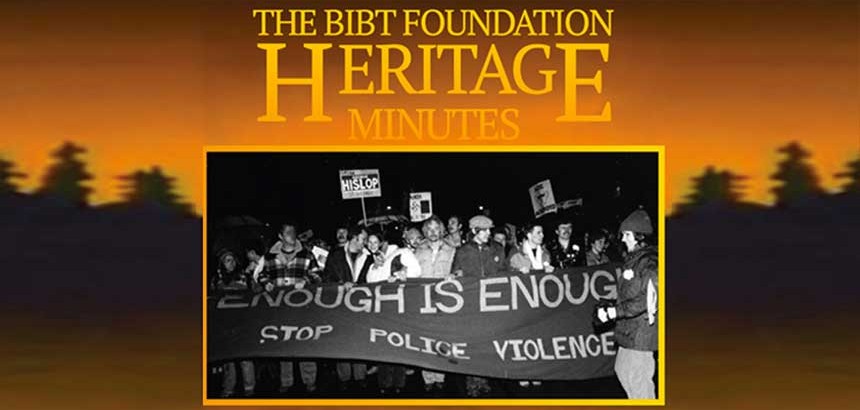

There are verities, as the three men discover. Following the line of inheritance, it becomes clear that the gay white male is at the top of the queer food chain, if such a thing could be said to exist. With palpable humility, they begin to explore the very contemporary idea of “staying in your own lane,” and privilege within a historically marginalized class. My favourite expression of this is when Atkins literally (figuratively) boards the Gay Heritage Bus. Upon warily taking a seat, he proceeds to converse with an assembly of non-white/queer/trans/lesbian/disabled characters, embodying them in turn. As one of them, he declares “You could be on any number of buses,” and after a beat, Atkins wonders why any of them have chosen this particular vehicle.

It’s a profound statement, not just about gay identification and its heritage, but the way that our ever finer need to define ourselves can cease to be liberating, and instead alienate us from one another.

Conversations with absent figures is used to great creative effect throughout. In fact, much of the drama is revealed through conversations with ghosts and abstractions, a highlight being Kushnir’s alleyway encounter with a triumvirate of rejected gay attributes: Drag, Camp, and Joan Crawford. Their world is a heavily populated one, and each performer enlivens the spectral characters with incredible wit and clarity.

And yet, it’s curious that as an ensemble they mostly engage with the material as solo performers, becoming audiences for one another in turn. It’s less puzzling when I think about how over its five acts, Atkins, Dunn, and Kushnir implement aspects of gay heritage to shape the production itself. The three performers are deft handlers of vaudevillian theatricality—singing, dancing, grinning out into the house. While they don’t say it explicitly, it formally speaks to gay heritage and the necessity of performance; necessity being the house mother of virtuosity.

The final and most solemn act, which acknowledges the human deficit caused by the AIDS crisis, casts new light on the choice to perform so many of the scenes with one man representing many. A defining feature of gay heritage is what (and who) can’t be seen or spoken to. It’s a beautiful gesture toward those who can’t speak for themselves—evoking Judy Chicago’s epic installation, The Dinner Party, an eternal banquet for women who will never have the benefit of dining there. And like Chicago’s work, The Gay Heritage Project is a feast recalling famine.

Related posts

Aurora Stewart de Pena on Allegiance

A Bibliography of Gay Heritage