Roberto Zucco by Bernard-Marie Koltès is the first show in Buddies’ 2024 – 25 season, running September 15 – October 5, 2024. Get tickets here.

Roberto Zucco, A Play About Roberto Succo

It was love at first sight when playwright Bernard-Marie Koltès saw the notorious Italian serial killer Roberto Succo’s wanted poster in the Paris metro. A year before Roberto Zucco premiered and Koltès died of complications from AIDS, Koltès said in an interview:

“There is a photo of him that was taken the day he was arrested, where he looks fabulous. Everything he has done is incredibly beautiful.”

– Bernard-Marie Koltès

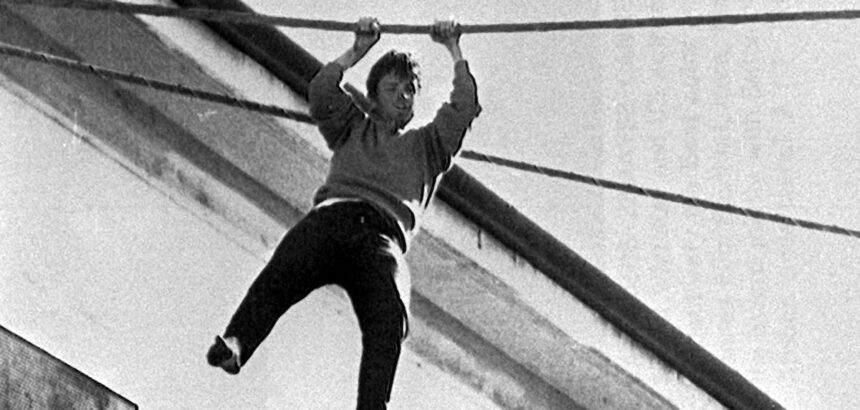

In March 1988, Koltès turned on his television and saw Succo on the roof of Treviso prison, where he’d climbed to after escaping his cell. Succo demanded that the prison guards summon the press, and for an hour and a half he monologued from the roof, stripping down to his underwear, ripping tiles from the roof and hurling them at parked cars.

“I could take five guards in my hand and crush them. I don’t do it, only because my only dream is the freedom to run in the street.”

– Roberto Succo

At this point, Roberto Succo had murdered his parents, stolen expensive cars, killed cops, escaped psychiatric incarceration, and crossed borders undetected. Watching the news footage of the killer on the roof as Koltès did, it’s hard not to believe what Succo says: he appears to us as a man who passes through prison walls, borders, identities, and names like water through a sieve.

After these brief encounters with the killer’s story, Koltès knew he wanted to write a play about Roberto Succo, but he was more interested in myth than documentary. In one interview, he said “no, I’m not investigating, I definitely don’t want to know more. This Roberto Succo has the great advantage that he is legendary.” The playwright started writing shortly after seeing the news of the Succo story, without much further research aside from the facts he’d heard on the news. He eventually titled the play Roberto Zucco, after an alias that Succo used to evade border agents when a warrant was out for his arrest under his actual surname.

Koltès finished the play in 1988, and died in 1989, one year before Roberto Zucco’s premiere in April 1990.

HIV and AIDS, Art Making, and Rage

While Koltès lived with the reality of HIV and AIDS in Europe, visual artist David Wojnarowicz (pronounced Wuh-nyar-o-wits) was creating work across the Atlantic, rising to prominence in New York City as both a boundary-defying artist and impassioned AIDS advocate, with much of his work centring around rage against the systems that were failing (and killing) him and his friends and loved ones.

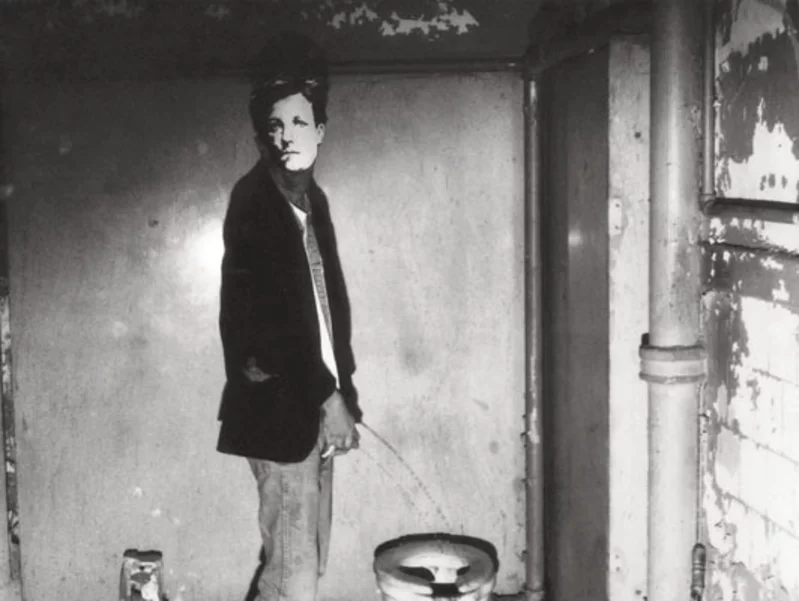

In 1978, before his work was widely recognized, Wojnarowicz took a series of photographs titled Arthur Rimbaud in New York. Wojnarowicz’s friend wears a paper mask with tiny eye holes, stencilled with the face of the poet Arthur Rimbaud. Rimbaud (1850 – 91) was a rebellious surrealist poet who defied tradition and rejected the constraints of Christianity, the heterosexual nuclear family, and the bourgeoisie.

In Wojnarowicz’s photos, Rimbaud hangs out at the piers, rides the subway, shoots up, jerks off. Through this series Wojnarowicz conjures Rimbaud into the present of the 70’s. Alongside these photos he wrote:

“When I was younger and living among the city streets I assumed the smoking exterior of the convict. I entered the shadows of mythologies and thieves and passion: the bedroom of waterfront nights where nameless men lay blooming along the floorboards; where meals and cots and train tickets could be found in a stranger’s hip pocket, and nothing was lost but slender minutes. Now, years later, having followed other roads, I still don’t believe in systems of order, policemen or borders.”

– David Wojnarowicz

An ocean away, Wojnarowicz was untangling the same absurd systemic violence in his work that Koltès found so abundantly in his mythologization of Succo.

The Queer Art of Roberto Zucco

Roberto Zucco isn’t a queer play in any immediately obvious way. The characters are by and large heterosexual, and Zucco stresses again and again how much he loves women. Too much. But at the heart of Roberto Zucco is an explicitly queer proposal; that a life of criminalization, poverty, and marginality is preferable to a life spent reproducing the bourgeois nuclear family.

“…I’m against the State and the government, they’re rotten… This prison sucks, it’s a dump. And now I’ll show you how the paratroopers do it.”

– Roberto Succo

In the video of Succo on the roof of the prison that caught Koltès’ eye in 1988, you can see him step off the roof onto a power line, shimmying across it toward the prison walls. And just as he reaches out with one foot to brace himself, he falls.

In the play, we are told again and again that the character Zucco — as a killer, as a myth, as a concept — is inevitable. A train that won’t leave the tracks, a rhinoceros marching through the mud. In Zucco, Koltès writes about the social inevitability of violence — the ruling class wields violence (through police brutality, patriarchy, and the reification of the nuclear family, for example) at such a massive and institutional scale that it becomes part of the social fabric. The playwright examines — through the reimagining of a very real, very violent figure — how people respond to institutional violence with individual and interpersonal acts of violence that replicate the structures in which they live, but are labelled as a marginalized minority in order to protect the legitimacy of state sanctioned violence. Koltès says:

“If we have to talk about the marginalized in terms of violence, it’s them. The real weirdos, the real weird people, are the provincial bourgeoisie. I wanted to show that it is the others who are not considered marginal, who are crazy, murderers. When we talk about violence in my plays, I say, we’re surrounded by that. The drivers in their cars are astoundingly violent, rude, and vicious, they are ready to kill everyone.”

– Bernard-Marie Koltès

David Wojnarowicz died of AIDS-related complications in July 1992. Before his death he wrote:

“as each T-cell disappears from my body it’s replaced by ten pounds of pressure ten pounds of rage and I focus that rage into nonviolent resistance but that focus is starting to slip my hands are beginning to move independent of self-restraint and the egg is starting to crack america america america seems to understand and accept murder as a self-defense against those who would murder other people and it’s been murder on a daily basis for nine count then nine long years and we’re expected to pay taxes to support this public and social murder and we’re expected to quietly and politely make house in this windstorm of murder but I say there’s certain politicians that had better increase their security forces and there’s religious leaders and health-care officials that had better get bigger fucking dogs and higher fucking fences and more complex security alarms for their homes and queer-bashers better start doing their work from inside howitzer tanks because the thin line between the inside and the outside is beginning to erode and at the moment I’m a thirty-seven-foot-tall one-thousand-one-hundred-and-seventy-two-pound man inside this six-foot body and all I can feel is the pressure all I can feel is the pressure and the need for release.”

– David Wojnarowicz, Close to the Knives

Bernard-Marie Koltès died of AIDS-related complications in April of 1989, one year before the first production of Roberto Zucco. Roberto Zucco isn’t a play about being queer. It’s a play about people on the margins of bourgeois society who seek each other out in abandoned subway stations and busy city parks. It’s a play about leaving behind the stability of the nuclear family for a chance at a few fleeting moments of self-actualization. It’s a play about hating cops and your parents, loving women, stealing cars and staying out all night until the day looks strange and alien and the world looks past you because you’ve seen the other side and you can’t come back.

Roberto Zucco is not utopian, not even optimistic. But it wedges possibility up against hopelessness. Maybe the guards don’t exist if you don’t look at them. Maybe the bars aren’t strong enough to hold you. Maybe if we all stopped believing in the fiction of prisons, police, borders, and families, they would fall away.

Pingback: Istvan Reviews ➤ ROBERTO ZUCCO ⏤ Buddies In Bad Times