Let’s make a canon! And let’s fill it with queer art, or queer-ish art, or art that has no idea how queer it is. Queer art is often secret art: black-market, whispered-about, read-between-the-lines art. And since secret art can be hard to find, let’s shine a light on a few of our favourite things so all our friends can see them.

We’ll call it a canon, because it sounds Weighty and Important and Serious, but we also won’t be too serious about it. We won’t make The Canon, just a canon. Each month, we’ll chat with a different queer-about-town and ask them to submit something to the canon. And they’ll tell us what that book or play or movie or TV episode or sculpture or poem or dance piece or opera or photograph or painting or performance art piece or anything else means to them and why they think it deserves a spot in our illustrious canon.

This month, we talked to actor and playwright Kawa Ada about Mary Renault and her novel The Persian Boy.

What did you settle on? Let’s hear it!

Do you know the novelist Mary Renault?

No…

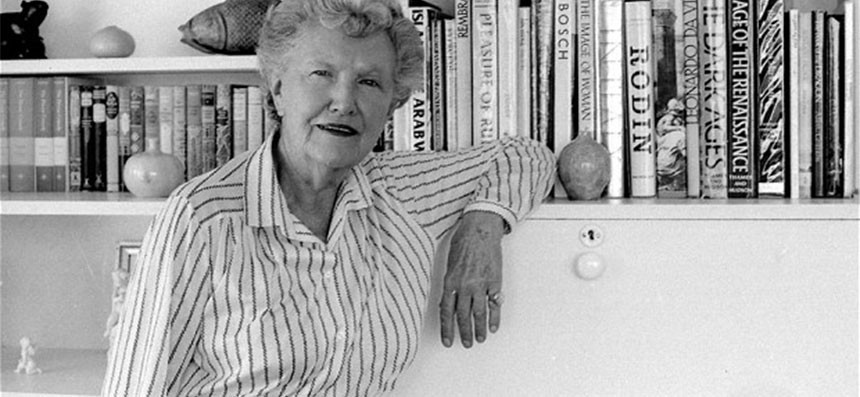

So, she was a British novelist who was born in 1905. She went to school to become a nurse. And then, when she worked at her first infirmary in London, this is around just before World War II, she met someone who would become her future lover. And they were both nurses. And that’s when Mary started to write these novels. And almost all of them have queer characters who are protagonists and queer relationships that are at their centre. What was groundbreaking about her is it was never questioned: it was not about liberation; it was not about pushing against something; the queer context was a given. Particularly within her historical fiction.

Right.

And the way that I got into her was through a book called The Persian Boy. And it’s about the Persian eunuch that was given to Alexander the Great by King Darius of the Persians as a gift. Alexander had him as part of his court, and he was second only to Hephaestion, his male lover/general. But his Persian eunuch was one of the great loves, and Mary Renault took that and wrote it with the eunuch as the narrator and central figure, because he’d always kind of been written as a minor character. And she lived in a time where—I mean, it wasn’t until the late 1960s that homosexuality became decriminalized in Britain. So, she was writing and living in a time when obviously that was a major barrier. But, to be able to then write historical fiction and write about a time when that was not a barrier, it was in fact part of the sexual spectrum that people lived within. So she could then move beyond that and actually write about the complexities of the relationship. I used to be obsessed with Alexander the Great—this is me at thirteen. And I’m doing all this research on Alexander the Great and I found out about this Persian eunuch. And I became obsessed with this Persian eunuch! And then years later, after I had kind of moved on, I found this novel: The Persian Boy—I had no idea what it was going to be. And then I realized that it was historical fiction based on Alexander the Great and this relationship… it was magic!

It’s like that book was looking for you!

I couldn’t believe it! And I devoured it. But it’s this fascination… I can’t even tell you why, but it’s this fascination with Alexander the Great, his legacy, and this relationship with this eunuch. And particularly because it was a Persian eunuch, which is my ancestry, so obviously there are some narcissistic elements in there.

Plus, how many times do you even get to hear a story about a eunuch?

Exactly! So, I did more research on Mary Renault, and what I ultimately wanted to talk about is: so she got a huge prize, the MGM Book Prize, and she moves to South Africa with her lover. Because she didn’t feel as comfortable in Britain. So, she moves to South Africa, where there are a lot of other ex-pats who feel they can live more freely there, and she becomes part of the Black Sash, which is a movement of white women who were anti-Apartheid.

Whoa! What an interesting life!

And that’s what I found so fascinating. Because one of the things that I’m kind grappling with right now is the feeling that the more power and privilege that we gain in any kind of under-represented or marginalized community, what are the responsibilities of that community to others that are still without power and privilege? And so, seeing her go to South Africa and become involved with this movement, being herself someone who had to deal with barriers, certainly, as a woman as a queer woman…

Yeah, it’s not like everything was hunky-dory for her.

She’d had her power and privilege marginalized by virtue of those identities, but The Black Sash movement, one of their major tenets was: as white women, we have certain natural privileges to be able to speak out against Apartheid without concern of recourse. So, it’s one of those things that, as the queer community here gains more power and privilege, how much responsibility do we have to other identities? With Black Lives Matter in the states, if there were more voices in the white community, more white politicians saying “black lives do matter” instead of saying “all lives matter…” When you gain more power and privilege, I do think it’s your responsibility to speak up for others who are still fighting for the same power and privilege that you have gained. It’s not about who’s gained more or who has less, it’s about continuing to pull each other up.