All month long, buddies is hosting a blog salon with some our favourite writers and artists responding to one question: How do I connect with my queer heritage? Follow the conversation on our blog, or join the conversation on Facebook and Twitter with the hashtag #GayHeritageProject. Here’s an entry from writer, artist, and one-half of Xtra’s History Boys, Michael Lyons.

A Time Capsule of Queer Iconography: Images, memories, heritage

![]() A tomb that has remained unopened for almost two millennia is discovered by archaeologists. Once inside they marvel at the iconography adorning the tombs. Two men are depicted in intimate embraces, like the resting place of a husband and wife. Those who first discovered the tomb of Niankhkhnum and Khnumhotep likely had little context to read into their discovery. Luckily for us, the adage about how much a picture’s worth holds true.

A tomb that has remained unopened for almost two millennia is discovered by archaeologists. Once inside they marvel at the iconography adorning the tombs. Two men are depicted in intimate embraces, like the resting place of a husband and wife. Those who first discovered the tomb of Niankhkhnum and Khnumhotep likely had little context to read into their discovery. Luckily for us, the adage about how much a picture’s worth holds true.

I’ve written about the tomb of Niankhkhnum and Khnumhotep before. One of the reasons I adore their story is it provides insight into the power of images for queer people. I was struck by this theme in the works of my fellow Gay Heritage Project bloggers. When queers see something they aren’t represented in, the find themselves in the subtext. If they can’t find themselves in the subtext, they subvert the image before them.

Images mean a great deal to us, and they’ve always meant a great deal to me. Inspired by ideas of subversion and finding who we are in (ostensibly) heterosexual imagery, I’ve decided to ask myself to create a time capsule, a handful of queer imagery, and reflect on what each one means to me, and why I’m including it. This may include a few of my own humble offerings mixed in.

Nan Goldin, Misty and Jimmy Paulette in a Taxi, NYC, 1991, 30 x 40 inches

Shortly after I first picked up a camera (somewhat) seriously, I saw the Nan Goldin documentary I’ll Be Your Mirror in a workshop with photographer Chris Ironside. I was astounded by the frank, vibrant, brutal life of the photographer through her pictures. As a child I loved disposable cameras, but it wasn’t until recently that I picked up a camera again. If I could emulate the work of one photographer it would be Goldin and her seemingly effortless style of snapshot photography, intimate portraits of friends, family, lovers, the comedy, tragedy, and queer culture that surrounds her.

Pierre et Gilles Naufragés, Fabrice, 1986

The first time I walked into Glad Day Bookshop I remember seeing a poster sized print of Pierre et Gilles’ famous “Mercure” propped up in a corner (I believe I’ve seen it around the store throughout the years since), though I had no idea what I was looking at, the iconic place their work has in gay culture. I adore their mix of the erotic with the artistic, their mix of mythology with pinups, certainly a gay aesthetic if I ever saw one. The work of Pierre Commoy and Gilles Blanchard is so rich and extensive I haven’t even started to delve into their lives and work in my own.

Drama queen, taken by a friend backstage, 2003

This, I suppose, is the standout piece in the bunch. The ghost of Christmas past (literally). I present a portrait of the author as Uncle Billy in a high school musical version of It’s A Wonderful Life; apparently one night of the run I snuck a disposable camera backstage to take pictures of my friends and castmates. I played the alcoholic screw-up, despite having never touched a drop at that point in my life. I had a solo, despite questionable singing talent. I was fat, queen-y, confused, Catholic, bullied, a little lonely. I include this picture as a nod to where I am from. This, likely above all else, informs my queer heritage.

Henry Scott Tuke, Noonday heat, 1902

Tuke was 19th century English painter who loved teen boys. While certainly a physical attraction, there are no known reports or incidence where this was sexual, but from his extensive paintings of young maritime boys, most famously “August Blue,” it’s clear that he luxuriated in their soft, almost iridescent forms. To me, “Noonday heat” is steeped in a subtle eroticism, the way the boys sprawl in the sand, gazing at one another, the hands almost touching. Many of Tuke’s models would eventually be called off to fight in the Great War. Many would never return.

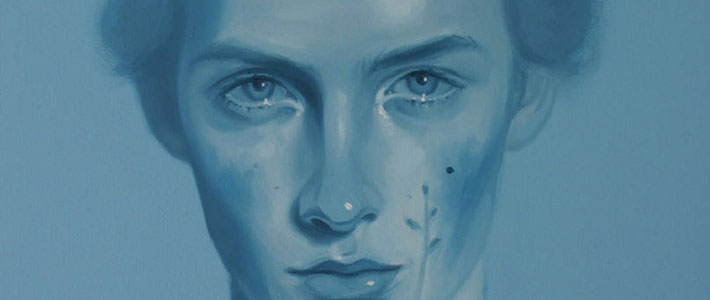

Kris Knight, Blue Moon, 2012, Oil on Canvas, 14 x 18 inches, Private Collection

I recently had the pleasure of interviewing Mr. Knight in his studio, an arrangement of his beautiful dream boys leaned up against one wall. Over a cup of tea he explained to me, “I like someone who is a myth, the idea of perfection, but you can tell just by their eyes that they are struggling.” Simply: sexy, sad, pretty boys. Why do sad boys appeal to us (Knight, Lyons, et al.), especially as artistic subjects or narratives? Is it that there is something sad about creating pieces of art, or is there something sad about beauty, or something beautiful about sadness?

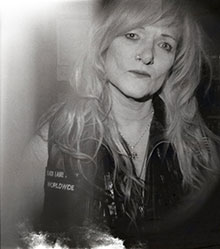

Patricia, 2011, Diana F+ with 400ISO B&W film

This is my favourite picture that I have ever taken. If it’s not already obvious, I covet portraiture. I first met musician and Buddies bartender extraordinaire Patricia Wilson as part of PrideCab 2008, when we interviewed “elders” as part of the process. I remember being both enchanted and terrified by her. I specifically remember, though I paraphrase, her describing a love-hate (mostly love) relationship with twinks on bar nights. How, even though they often annoyed the shit out of her, they were being themselves, and that was wonderful to her. I’m a shy person, but a few years later I gathered up the courage to march up to her with my camera and ask if I could snap a picture of her. She gave me that badass, “fuck you” stare, but let me. The picture, as a mentioned, is my absolute favourite, and probably always will be. I place it proudly into my time capsule.

James Bidgood’s Pink Narcissus appeals to me for the same reason Tom Ford’s adaptation of Christopher Isherwood’s A Single Man does. Or maybe for similar reasons why everything I’ve provided for my queer image time capsule does. It’s a stylistic, quiet closeness, a moment that is highly charged. I remember the first time I saw this scene, likely this exact YouTube clip, I vowed I had to know everything about that song and that movie. What I figured for a nostalgic siren song turned out to be the androgynous crooning of Harry Babbitt to Kay Kyser’s big band song, “Thinking of You.” The aggressively colourful, erotic world of Bidgood’s young hustler enraptured me: the melding of fantasy, loneliness, and sex. I have a DVD copy now, actually. I’m waiting for the day that I can host a screening, maybe put together writings about this mysterious little film. Hopefully, from the clip, you may understand why.

There is my time capsule, small and imperfect as it is. As a queer person I am constantly reading into things, pictures, songs, paintings, searching for some illusive meaning. Images help us map out our lives, and what has come before. I love how much we all read into the images around us, and that my fellow bloggers seek out meaning in them. I think as queer people, our power is to always see something different in them.