A few words about a grandmother, a grandson, and a funeral that should have been grand, but was what it was.

Peggy Mackay Macdonald was what kids these days would call fierce AF, and a charming grandmother. Eternal love and respect.

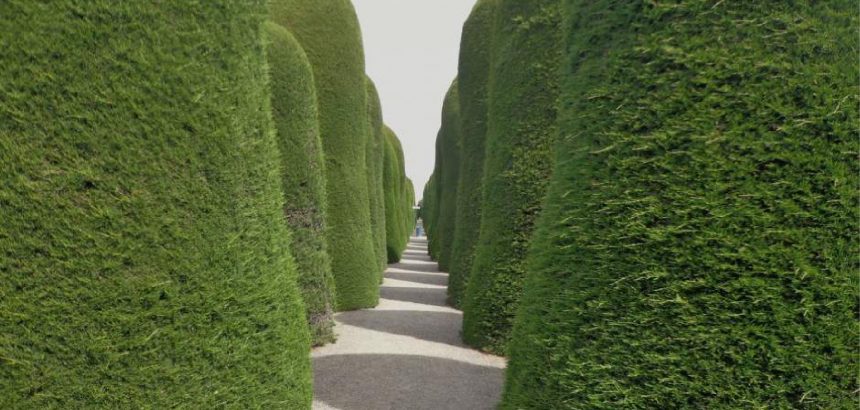

Punta Arenas is where she spent most of her life (the southernmost city in the continent, in Chilean Patagonia), after running a sheep farm with my grandfather. One of the things I love most about the city is that it has the most beautiful funerals I’ve ever known. The cemetery—pictured above—is one of the city’s biggest tourist attractions). After a funeral service, the deceased’s family would carry the coffin together on a cart to the cemetery. They are followed by a procession. In my family’s case, it’s a half-hour procession from Saint James Church (where the Protestant Scottish-Chileans go) to the burial ground: quite a way to go on foot, quite a way to say goodbye.

Back to origins.

Grandma always enjoyed telling me how she and my grandfather met, how he proposed, and what she did with that.

Their meet-cute: at a sheep show (something like a winter fair, but with sheep appraisals). A few dates later, my grandfather, John Fell Rudd (whom I sadly never met), invited Peggy to the movies to see Casablanca (keeping it classic). During the film, John popped the question, and Peggy said yes. I feel like I would have said, “I’m watching the movie, talk later….”, but that’s probably not true.

So, my mother and I kind of owe our existence to Bogie and Bergman, though I never asked during what scene this happened. 19-year-old Peggy then did the most modern thing. She told her father, “I’m marrying John Fell, and I AM NOT asking for your permission” (a true example of her fierceness for the early 1940s). She was so proud of this moment, and so am I.

Her life was a good, tough life, filled with love, loss, and generosity: I am grateful to have been exposed to extreme generosity like hers. An enormous gift, if not the best thing you can teach your grandchildren.

Peggy passed away a bit after the quarantine began, and right before her 95th birthday. There was no way to get to Punta Arenas (2,241.43 kilometers away from where I’m staying with my parents). Almost 100% of our family members shared the same situation (except for my aunt Helen).

So we attended my grandmother’s funeral on Zoom, and it was queer.

It’s very hard to write this.

Saint James Church was the stage: the same place where my parents got married, a small church at the end of the world.

For the funeral, the family met on Zoom a few minutes before, and had that “Hi, can you hear me?”, “You have to press where it says ‘Join Audio’” kind of dynamic. Before mass, we could see each other, and we could see ourselves on the screen. This doesn’t happen at funerals.

A ritual on Zoom is not something you can just watch, like digital, performative experiences nowadays. The participants are gathered in an assembly of sorts, like in live theatre: the ritual cannot happen without an audience that can sense each other. And yet, there’s a distance.

And the lighting was odd.

Had we been there, it wouldn’t have mattered.

And the sound, choppy.

“Please, turn off your microphones, or the sound will get all messed up.” How can you communicate that during mass?

And there were projections with verses and hymns, which were hard to read.

I’m also very self-conscious during hymn singing (back when I used to go to Church). The level of self-consciousness was larger here, but why?

Breathe in, let go, say your goodbyes.

There must have been ten people at the service. Everyone was wearing masks and gloves, sitting very far away from each other. I did get the chance—which I wouldn’t have during a live-attended ceremony—to ask my parents who the people there were. It gave us something to talk about later, celebrating Peggy’s memory with their stories.

My aunt was holding her cellphone during the ceremony, transmitting everything happening around her. I feel her right to experience the funeral personally was stolen by a virus, and it breaks my heart.

And there was no procession.

I don’t think Grandma had the funeral she deserved, but I know she would have wanted everyone to be safe. She knew that saying goodbye is hard in any shape or form. What would our existence be without it?

I asked my parents about the experience a few days ago.

My mom said she hadn’t felt alone. She felt her family, she felt a part of it in her heart. Was it strange? Of course, but she was happy it happened. I could not begin to imagine how the experience would be if I had been in her place, but I know I’d be somehow happy about it, too.

I guess the “it is what it is” is still something.

My dad said it was better than having done our own private ceremony or prayer at home. He felt we were part of this family’s chapter, and it’s something we should be grateful for.

They are right, no matter how bizarre it was to me.

It was a queer, important moment in our family history; and will be for many families to come.

Looking further back, there were no Zoom dynamics when my best friend, Carlos Montecinos Zapata, died in 2012. I had just arrived in Canada, he died in Chile, and I did nothing that meant closure. Maybe I wasn’t ready to say goodbye, perhaps I never will be, and I guess I’ll never know the effects of that ritual I never performed. What I do know: is that distance is physical, not emotional, and never spiritual.

I suppose it’s time to find space in our lives for these queer new things around us, as an act of generosity, and to, as Peggy would always say, “make the most of it.”

Play it again, Sam.

Zoom out.

Related posts

Exiled